IODINE GLOBAL NETWORK is a nongovernmental organization dedicated to sustained optimal iodine nutrition and

the elimination of iodine deficiency throughout the world.

Special Issue:

Progress against IDD in

West and Central Africa

IDD

NEWSLETTER

Iodized salt in

Mauritania

PAGE 7

West and Central

African salt trade

PAGE 10

Nigerian salt chain

analysis

PAGE 16

VOLUME 50

NUMBER 2

MAY 2022

2

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 IDD IN WCA

To contribute to the sustainable eliminati-

on of iodine deficiency disorders in West

and Central Africa, the United Nations

Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Iodine

Global Network (IGN) formed a part-

nership to support national and regional

efforts to scale up and sustain universal salt

iodization (USI). One initiative involved

carrying out a landscape analysis to develop

a common understanding of the situation

and of the bottlenecks at national and regi-

onal levels. In this special IDD Newsletter

edition focusing on the iodine program-

ming in West and Central Africa, some of

the findings from this analysis are presented

in a series of articles.

UNICEF's West and Central Africa

(WCA) region encompasses 24 countries

that spread across semi-arid areas in the

Sahel, large coastal areas on the Atlantic

Ocean and along the Gulf of Guinea inclu-

ding a few islands, as well as tropical forests

covering many countries (1). The region

is defined by diverse economic, social,

cultural, demographic, and geographical

characteristics. It uses four official languages

(English, French, Spanish and Portuguese),

with over a thousand local languages. In

2018, the regional population was 520

million, and the population growth for

the next 10 years was estimated at 2.6%

compared to 0.9% for the rest of the

world. With 12% of its population being

under the age of 15, WCA has one of the

youngest populations in the world (1).

The region is also experiencing accelerated

urbanisation, with urban centres hosting

48% of the population (2) and, due to the

high level of violence and political tension,

there are over 11.9 million people who are

either internally displaced persons (IDPs),

refugees, asylum-seekers or stateless (3).

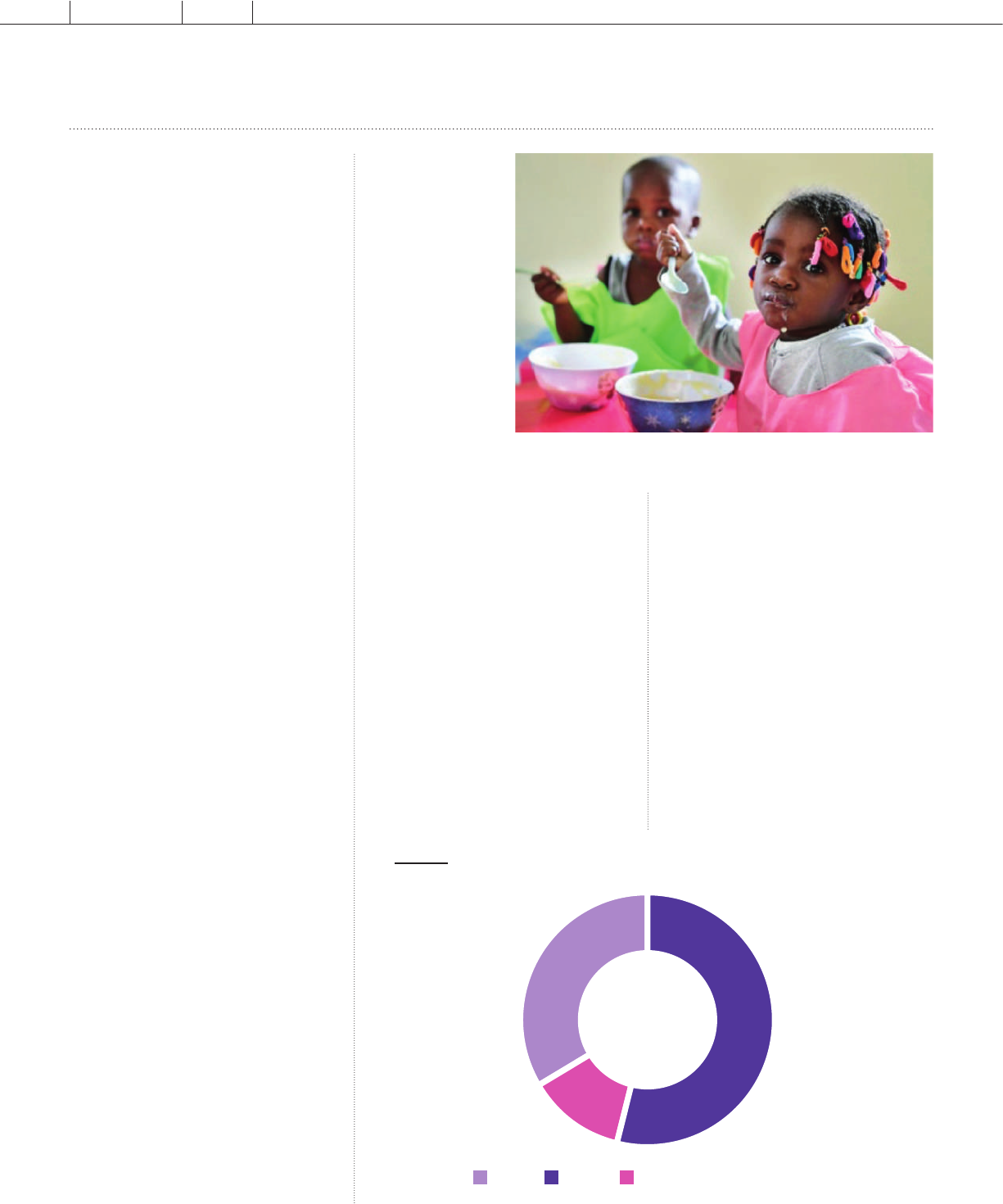

Regional trends in iodine status

and access to iodized salt

Globally, there has been tremendous pro-

gress over the past 25 years to prevent

iodine deficiency through USI (4), with

88% of households consuming iodized salt

(5); however, with a coverage of 76%, the

WCA region has the lowest proportion

of households consuming iodized salt

(> 0 ppm) compared to other regions, with

large discrepancies between countries. The

level has remained the same over the last

20 years with very few improvements. As

seen in Figure 1, only in eight countries

within the region,

is the proportion

of households con-

suming iodized salt

(any iodine > 0 ppm)

above 90%, and

in three countries

(Equatorial Guinea,

Guinea Bissau and

Mauritania) less than

40% of households

have access to iodized

salt. This data does

not show coverage

of adequately iodized

salt (> 15 ppm); this

can only be assessed

by quantitative

methods such as

titration and spectrophotometry. In recent

national surveys, only two surveys had a

quantitative assessment of iodine adequacy

in salt.

Currently, in the WCA region, school-

age children's median urinary iodine con-

centration (mUIC) varies greatly between

countries (Figure 2). Optimal iodine status

is observed in 16 countries, while three

countries, Benin, Cameroon and Equatorial

Guinea, have urinary iodine levels abo-

ve 300 μg/L (indicating excessive iodine

intake). Four countries, Burkina Faso,

Central African Republic, The Gambia and

Mali, have mUIC levels below 100 μg/L

(indicating insufficient iodine intake). This

data should, however, be interpreted with

caution since, for 20 countries, the data is

over five years old. Of concern, is that two

countries (Sao Tome y Principe and The

Republic of Congo) do not have any data

on their iodine status.

Furthermore, only four countries

presented sub-national data, and only

three countries provided disaggregation by

urban/rural residence, which is important

for exploring sub-national disparities and

inequities. For most countries, the availa-

ble data on iodine status is for school-aged

children only; however, the situation of

other subgroups in the population, par-

ticularly pregnant women, may differ. In

fact, in a recent study to assess the burden

of iodine deficiency in pregnancy in Africa

using estimated a pregnancy median urinary

iodine concentration based on school-age

Amal Tucker-Brown, IGN WCA regional coordinator, Arnold Timmer, IGN Senior Advisor and Anne-Sophie Le Dain, Regional Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF WCA

Children having a meal in the kindergarten at the development action center

of Guingreni, in the North of Côte d’Ivoire.

© UNICEF/ UNI372441/Frank Dejongh

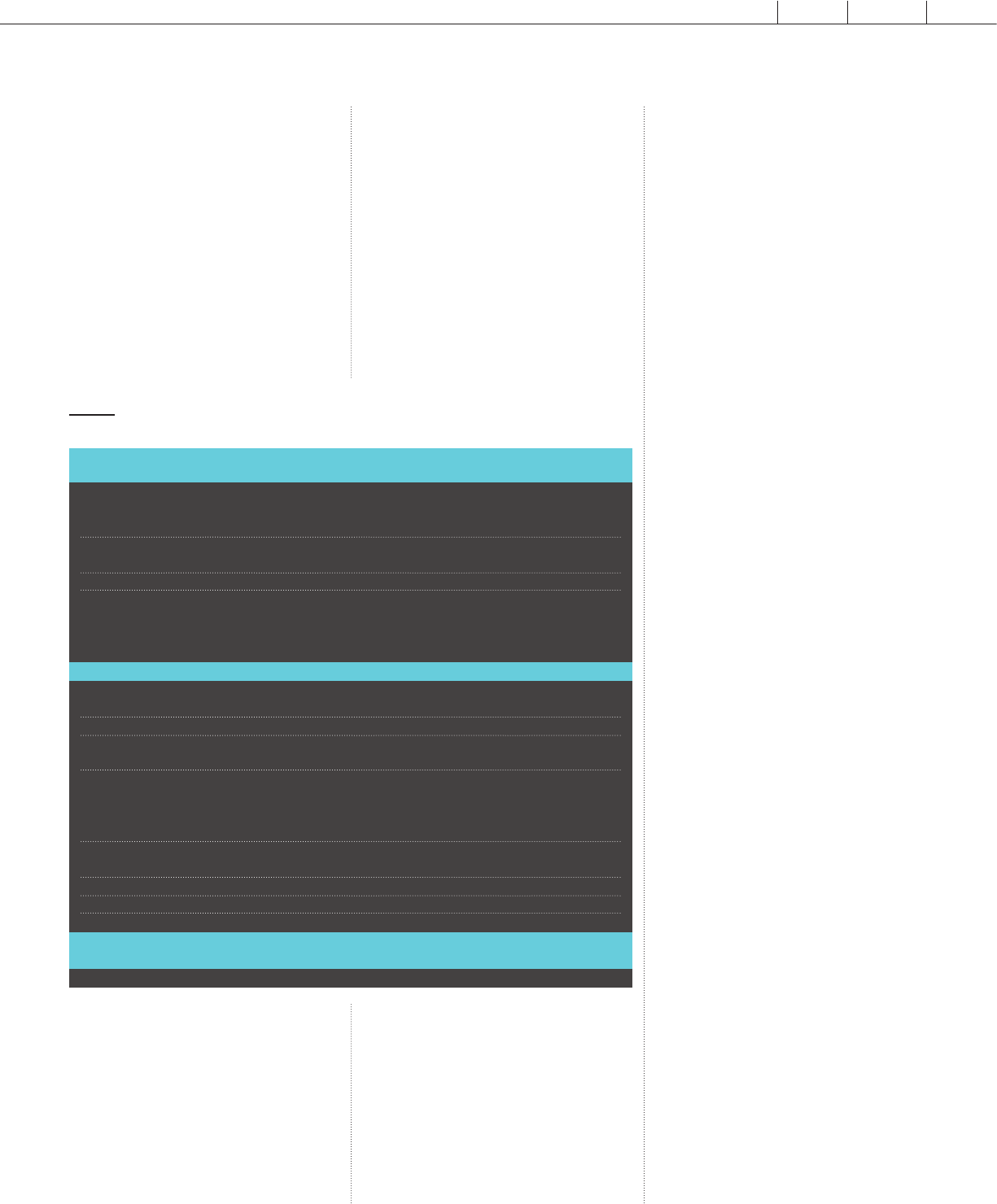

FIGURE 1

Coverage of household iodized salt (any iodine)

> 90 % of households

Benin

Cameroon

Cape Verde**

Congo*

Gabon*

Liberia*

Nigeria

Sierra Leone

40–90 % of households

Burkina Faso*

Central African Rep.

Chad

Côte d'Ivoire*

Dem. Rep. of Congo

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Mali

Niger

Sao Tome y Principe

Senegal

Togo

< 40 % of households

Eq. Guinea**

Guinea Bissau

Mauritania

> 90 % 40–90 % < 40 % * Data 5–10 years of age

** Data over 10 years of age

13

8

3

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 IDD IN WCA

3

children data, a cut-off school-age mUIC

≤ 175 μg/l correlated with an insufficient

iodine intake in pregnancy (mUIC ≤ 150

μg/l) (7). In the WCA region, eight coun-

tries had a school-age mUIC ≤ 175 μg/l,

which suggests that although school-age

children are iodine sufficient (8), pregnant

women are possibly iodine deficient. With

the increase in consumption of processed

foods it is significant to understand from

where the iodine is sourced, that is, from

iodized household salt or from processed

food made with iodized salt; this distinction

can be explored by stratifying mUIC by

household access to iodized salt. However,

in recent data only five national surveys

included this stratification.

There is a lack of updated

data in the region, and the

available data has insufficient

granularity for effective

monitoring and evaluation

of the USI program

In addition to the cost of large-scale

surveys, one of the main barriers to

assessing the population's iodine sta-

tus is the lack of laboratory capaci-

ty. There are only two countries in

Africa, namely, Tanzania and Ma-

dagascar, that are part of the CDC-

run Ensuring the Quality of Iodine

Procedures (EQUIP) program. This

is one of the largest standardisation

programs that addresses laboratory

quality-assurance issues related to

testing for iodine status. To increase

access to quality laboratories, there

is a need to increase the number of

laboratories as part of the EQUIP

program. These can act as reference

laboratories for the region.

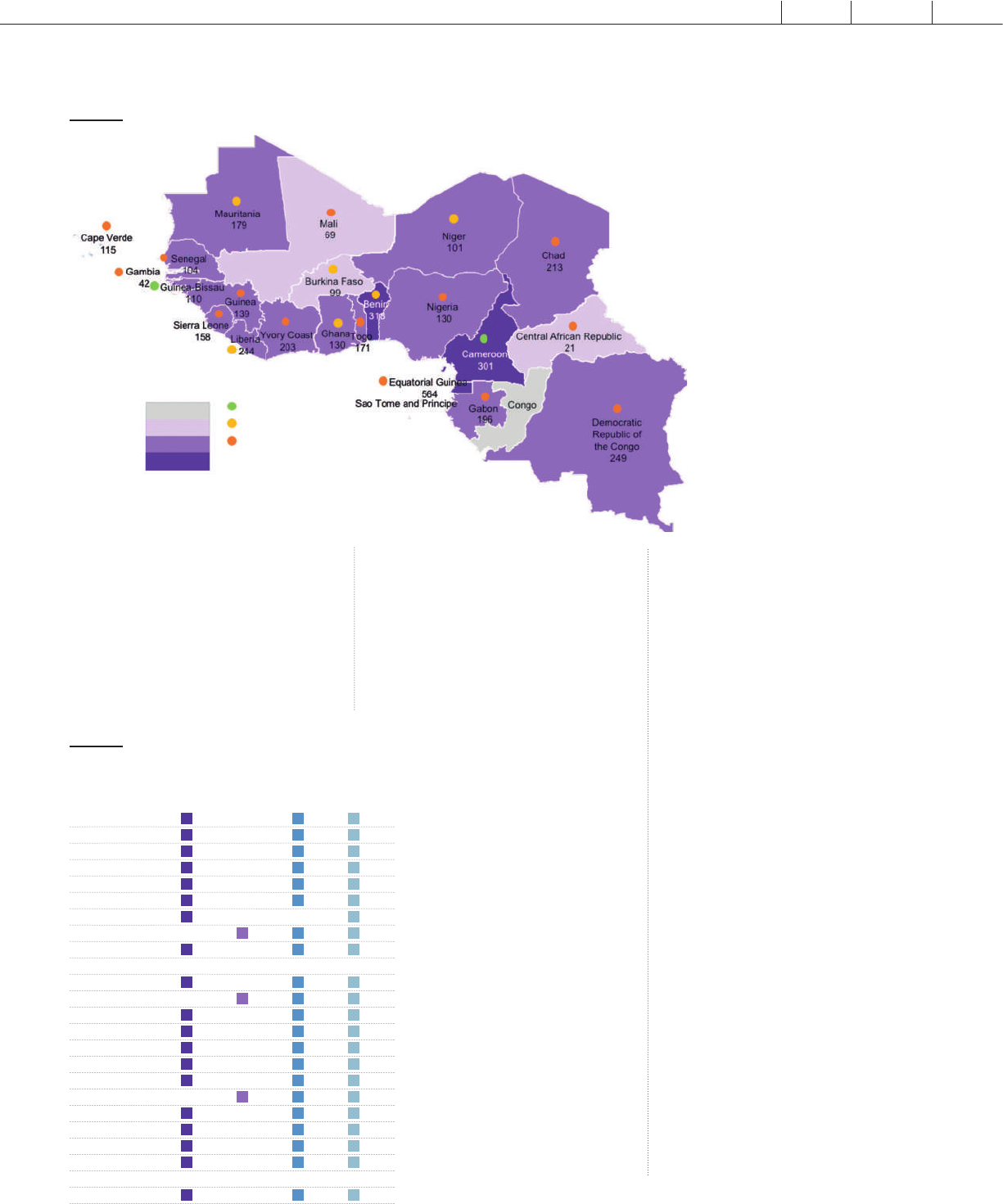

Policy landscape for USI

and salt reduction

All but two countries (Sierra Le-

one and Equatorial Guinea) have

adopted mandatory salt iodization.

However, the legislation has not

been updated in most countries

since it was drafted and, therefore,

is not in line with the Economic

Community of West African States

(ECOWAS) standards that were

drafted in 2015 to facilitate trade

of iodized salt between countries.

With regard to the scope of the

legislation/standards, of the 22

countries where salt iodization is

mandatory, all specified that dome-

stically produced and imported salt

should be iodized, including salt for

processed food; twenty mentioned

iodized salt for animal feed

(Figure 3).

Enforcement of the legislation

remains weak in most WCA coun-

tries. In salt importing countries,

the customs officers deal with lengthy and

porous borders that facilitate the illegal im-

port of non-iodized salt. In salt producing

countries, the salt industry is fragmented,

with multiple small and artisanal producers

located in remote areas, making regular

enforcement difficult to conduct. Many

different agencies are involved in quality

control management, inspection, compli-

ance and control. However, roles and re-

sponsibilities among the numerous agencies

are not clear and/or aligned in all countries,

despite 15 countries having multi-sectoral

alliances that guide and legislate fortification

activities. Nevertheless, the recognition of

the need for salt iodization is well expressed

as part of the various country-level food

and nutrition security policies, plans and

programs, as well as in food fortification or

micronutrient strategies and guidelines in

the region. However, of the WCA regional

countries, only two countries have active

specific action plans/strategies/programs

focusing on salt iodization (Gabon and

Mauritania). The landscape exercise has

reinvigorated the USI program in some

countries as six new actions plans have been

drafted (Chad, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali,

Mauritania and Sao Tome et Principe).

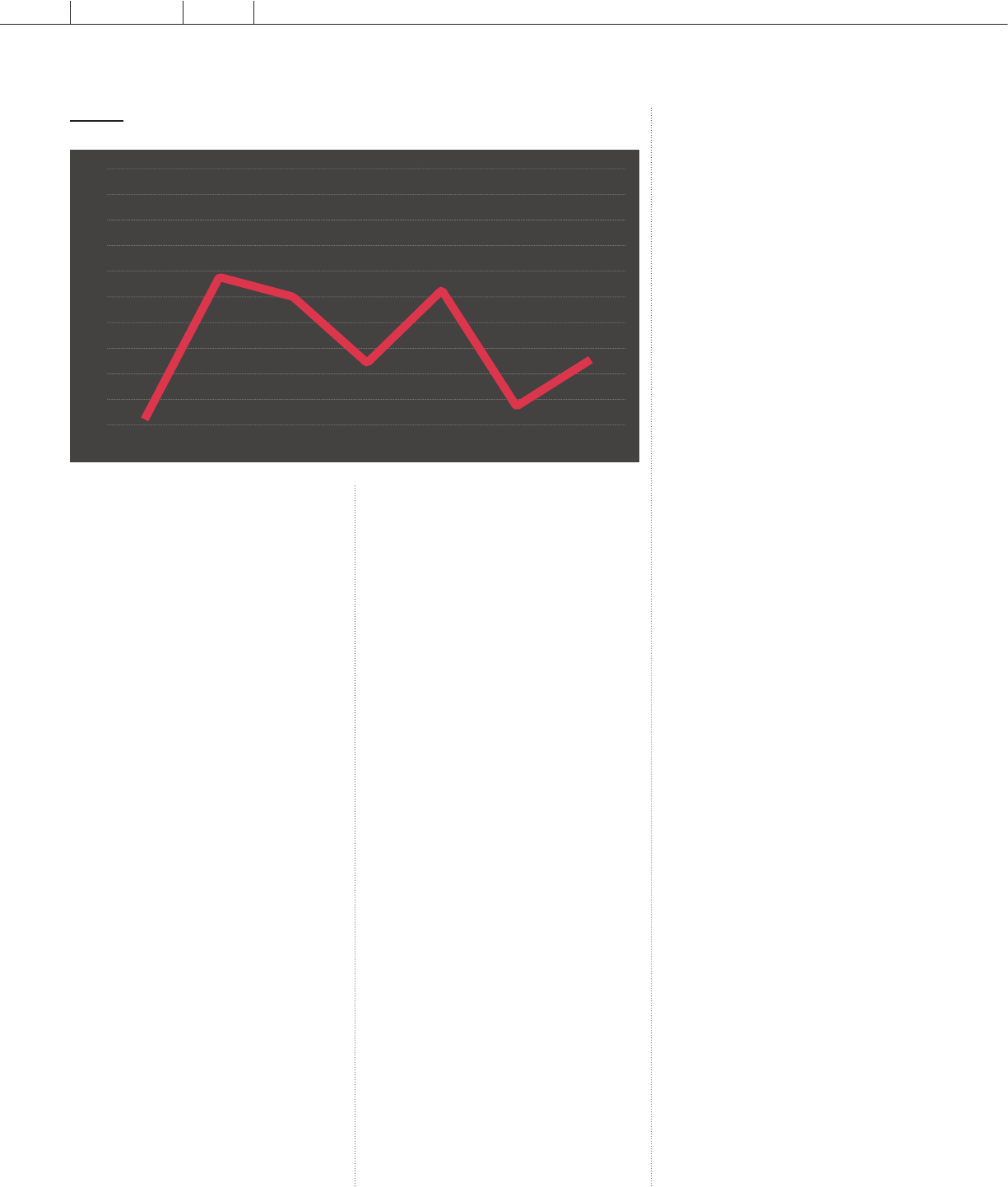

After 30 years of programming, the interest

in USI has waned; Figure 3 shows a chro-

nogram of the last national activity/event

for USI in each country.

FIGURE 2

Median urinary iodine status of school-age children in West and Central Africa (6)

Median Urinary Iodine Concentration

Not available

<100 µg/L

100–300 µg/L

>300 µg/L

Date of the survey

<5 years

5–10 years

>10 years

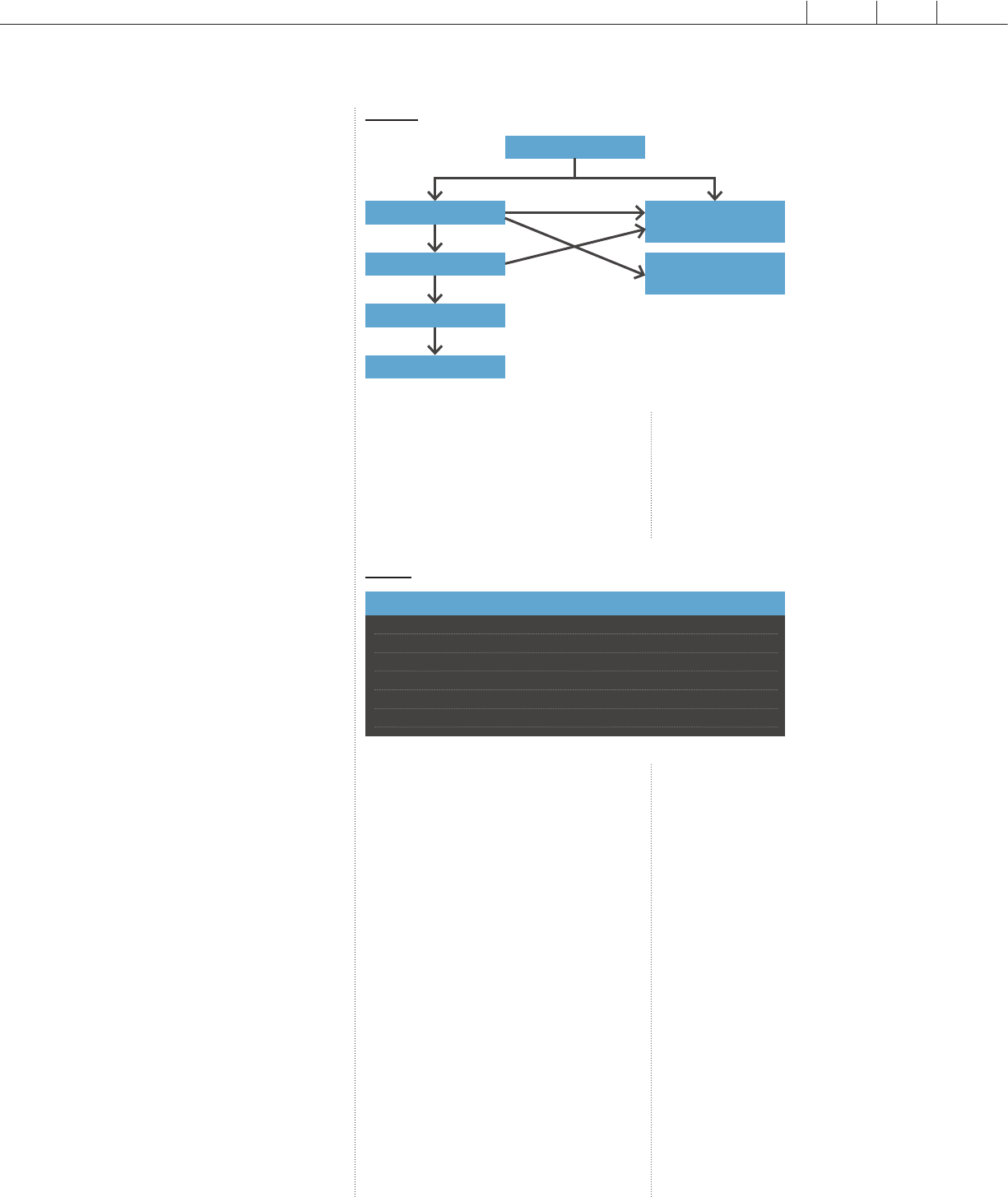

FIGURE 3

Scope of salt iodization legislation

in West and Central Africa (9)

Benin

Burkina Faso

Cameroon

Cabo Verde

Central African Rep.

Chad

Republic of Congo

Côte d'Ivoire

Dem. Rep. of Congo

Equatorial Guinea

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea Bissau

Liberia

Mali

Mauritania

Niger

Nigeria

Sao Tome y Principe

Senegal

Sierra Leone

Togo

All types Excep- Domestical- Import

tions ly produced

4

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 IDD IN WCA

For some countries, the last major national

activity/event dates to 2002; therefore,

there is an urgent need to reinvigorate the

regional interest in USI. Finally, countries

are developing salt reduction strategies

that should be implemented hand in hand

with salt iodization. To date, in the WCA

region, only four countries (Central African

Republic, Guinea Bissau, Nigeria and

Senegal) had salt reduction policies/strate-

gies or programs, and none were linked

to the USI program.

Salt production and trade

Only three countries have the natural

resources to produce salt in large enough

quantities to be exported. These are Ghana,

Senegal and Mauritania; however, Sene-

gal remains the largest exporter of salt in

the region. Other countries in the region,

namely Benin, Cape Verde, Chad, Gabon,

Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mali,

Niger, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, produce

smaller quantities of salt that is for locali-

sed use only; this salt is often not iodized.

Many producers in the region produce

poor quality and poorly iodized salt, if

iodized at all. This is mainly because the salt

industry is fragmented and characterised by

many small and artisanal producers that a)

are not committed to salt iodization, or b)

when they are, struggle to procure potassi-

um iodate and iodization equipment. Fre-

quently, they do not apply rigorous internal

quality control procedures due to a lack of

capacity and economic power to make the

necessary investments. Coupled with weak

enforcement, there is no repercussion for

their lack of iodising salt.

Details of the main salt producing countries

are described in the text box. (10)

FIGURE 4

Last USI event per country in West and Central Africa

Salt production in Senegal

With a coastline of more than 700 km and a series of flooding inlets, Senegal

has an enormous potential for salt production (10). Indeed, Senegal is one of

the biggest salt producers and exporters in the sub region, however, the salt sector

remains a very diversified and complex arena where a large single industrial

mechanised producer and one medium-scale industrial factory are responsible for

50–60% of the total salt produced per year; the rest (30%) is produced by over

15,000 artisanal producers that often operate informally at many traditional

collection sites. Iodization is carried out at the demand of the buyer purchase

of the salt.

Salt production in Ghana

Ghana is one of ten salt-producing countries in Africa and with its coastline of

573 km the country has the potential to produce approximately 3,000,000–

5,000,000 MT per annum; however, currently it is only producing 300,000–

350,000 MT of which 60–70% is exported, mainly to Burkina Faso, Niger, Togo,

Cote d’Ivoire and Benin. In 2013, 60 per cent of the salt output was processed

through modern methods, mainly by the medium-scale and some of the small-

scale producers who have the capacity to iodise, while the remaining 40 per cent

was processed through artisanal methods. Across the medium, small-scale and

artisanal categories of salt producers the preferred method for iodization is the

knapsack sprayer method which does not allow for homogenous iodization of the salt.

Salt production in Mauritania

The main type of salt produced in Mauritania is rock salt which is extracted from

three sites with an annual production of 31,000 tonnes per year. Wholesalers

in Nouakchott can iodise the salt at the request of the buyer. However, iodiza-

tion is rudimentary and is carried out using a plastic bottle with a hole in the top,

so that iodine distribution is not homogeneous. Salt from Mauritania is mainly

exported informally to Mali; however, there are talks to start exporting to other

countries in the region (11).

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 IDD IN WCA

5

In addition to these main salt producing

countries, Nigeria, Cameroon and Ga-

bon procure raw salt, refine and iodise it,

and then export the higher-grade salt to

neighbouring countries and beyond. A

more detailed description of the salt trade is

available in this issue of the IDD Newslet-

ter.(11)

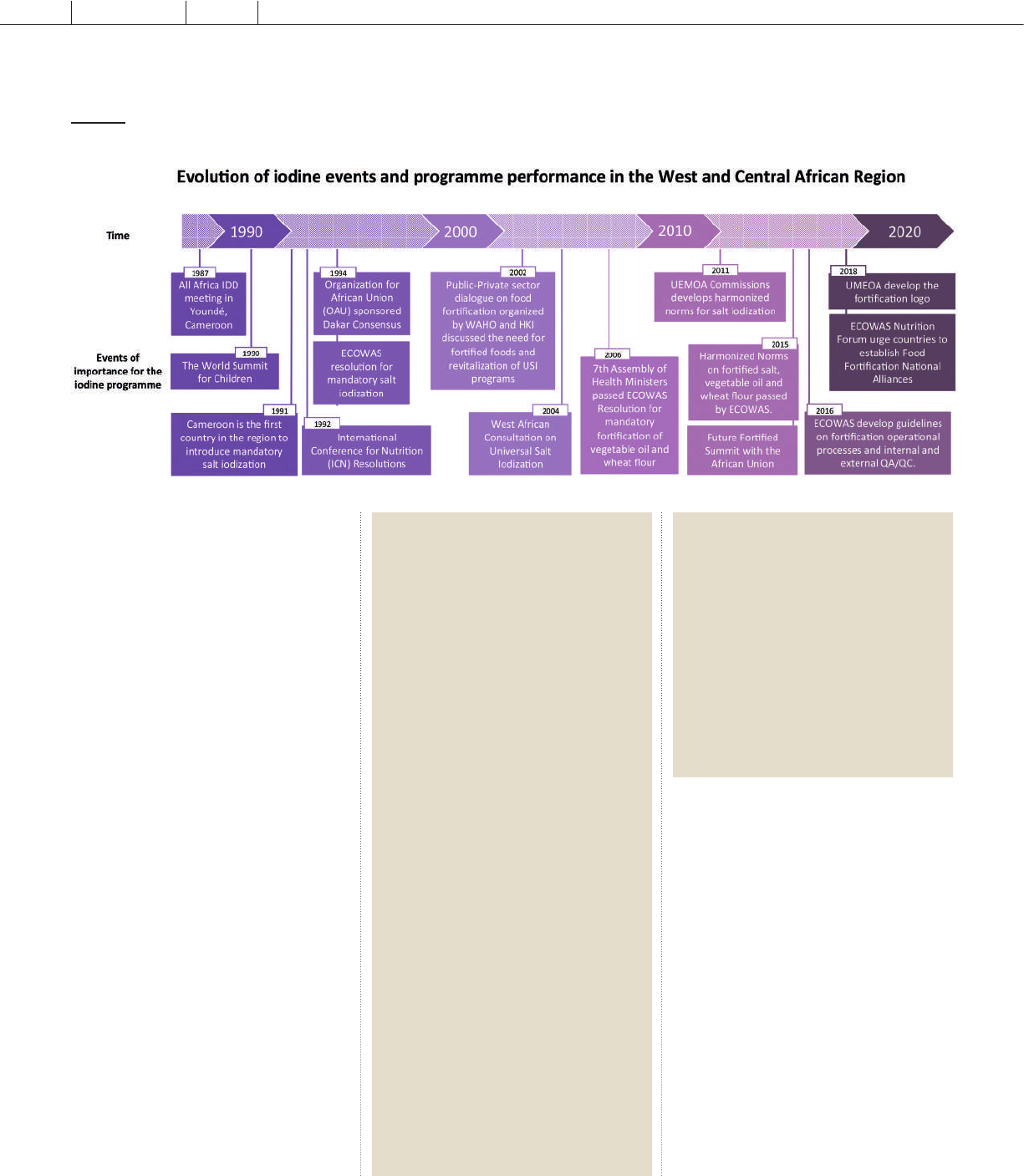

Considering that most of the coun-

tries in WCA are salt importing, there is a

need to develop a symbiotic relationship

between salt importing and salt producing

countries. Salt importing countries de-

pend on the success of the salt iodization

programs of the salt producing countries

to supply quality iodized salt, and the salt

producing countries depend on the success

of the salt iodization programs in the im-

porting countries to demand quality iodized

salt (Figure 4).

Other sources of iodine in the diet

Global guidance around salt iodization has

mainly focused on adequate iodization of

household salt. However, with accelera-

ted urbanisation and rapid industrialisati-

on, there is an increased consumption of

industrially processed foods. This shift in

dietary patterns has resulted in processed

foods accounting for an increasing propor-

tion of total salt intake and subsequently

iodine intake if the salt is iodized. Even

though, ultra-processed and processed foods

should be minimised in household diets,

legislation should ensure that the iodization

standard should move from solely focusing

on table salt to ensure all

salt for human consump-

tion is iodized without

exceptions. The presence

and levels of iodine in salt

used in processed foods are

often unknown and should

be monitored to ensure

that salt consumption is

regulated and iodine status

remains within the optimal

range (12). The results of

a recent study (13), con-

ducted by IGN to assess the

consumption, production

and supply chain dynamics

of major sources of salt from

processed foods in West

Africa have significantly

shown that, processed food

made with iodized salt can

greatly contribute to the

iodine status of the popula-

tion. USI includes salt for animal feed; ho-

wever, there is little information on the use

of iodized salt for animal feed, which could

also become an important source of iodine

in the diet and improve the overall health

and productivity of the animals. Further

research is needed on the use of iodized salt

(or supplementation) in industrially produ-

ced animal feed in the WCA region.

Regional efforts toward strengthe-

ning and sustaining USI

To increase their collective influence,

countries within the WCA region have

combined into several regional economic

communities that could be leveraged to

support USI. In West Africa, as the official

health body of ECOWAS, the WAHO has

been key to advancing food fortification

since the USI resolution of 1994 (14). In

addition, the West African Economic and

Monetary Union (UEMOA), despite being

a monetary union, has also been highly

active in promoting food fortification,

including USI (14). Details of the main

regional activities are illustrated in Figure

5. Much of the regional work is limited to

countries in ECOWAS and, in some cases,

further limited to countries in UEMOA

only. Little, if any, regional work has invol-

ved the countries in Central Africa; more

engagement with the Economic Commu-

nity of Central African States (ECCAS) is

needed to ensure the supply of iodized salt

from West to Central Africa.

The political will and commitment of

regional health and economic bodies have

been critical to launching food fortification

across West Africa. Through the leadership

shown by these bodies, national govern-

ments abided by resolutions and recom-

mendations to initiate and mandate food

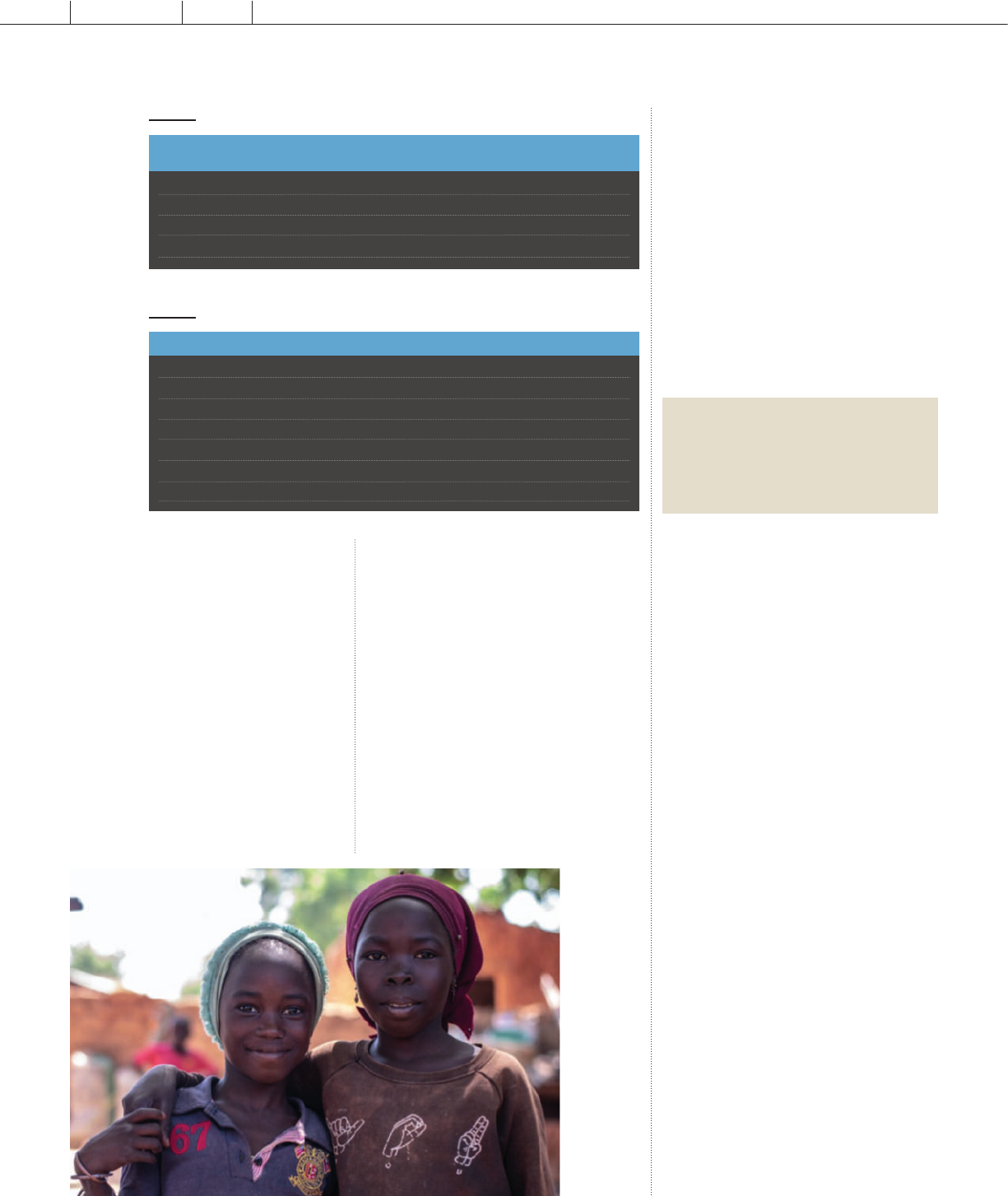

Aerial view of the pink Lake Retba or Lac Rose in Senegal.

Salt industry in West Africa.

©Photo by Curioso Photography on Unsplashed

FIGURE 5

Symbiotic relationship between salt importing and salt producing

countries in West and Central Africa

6

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 IDD IN WCA

fortification, including USI (14). However,

in the last 10 years, there has been limited

regional coordination and management by

these regional bodies in USI. Furthermore,

the issue of salt iodization in WCA is more

of a trade issue and, therefore, beyond the

scope of health alone.

In conclusion, the high coverage of

iodized salt and adequate iodine status has

culminated from a series of country-level

efforts spearheaded by regional support and

enhanced by national capacity to monitor

the USI program and enforce legislati-

on. However, in the last 20 years, there

has been little advancement in the USI

program performance in the WCA region

and little activity at the regional level in

the last 10 years. There is a risk that the

gains achieved to date may be reversed

if a conscious effort on USI is not made

considering the changes in the current

situation and lessons from past experiences.

There is a need to adopt an increased food

systems approach to USI programming; an

approach that considers all the elements

along the whole salt supply chain, including

their relationships and related causes and

effects. This will enable program mana-

gers to address today's gaps and adjust to

tomorrow's challenges through strengthe-

ning national positioning, improving

program management, including monito-

ring, assuring a stable supply and demand

for adequately iodized salt and focusing on

regional networks.

References

1. The World Bank. The World Bank in Western

and Central Africa [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020

Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.

org/en/region/afr/western-and-central-africa

2. UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children

2019. Children, Food and Nutrition: Growing

well in a changing world. 2019.

3. UNHCR. Update on UNHCR’s operations in

West and Central Africa - Feb 2022. 2022.

4. Gorstein JL, Bagriansky J, Pearce EN, Kupka

R, Zimmermann MB. Estimating the Health and

Economic Benefits of Universal Salt Iodization

Programs to Correct Iodine Deficiency Disorders.

Thyroid. 2020 Dec 1;30(12):1802–9.

5. UNICEF Global Databases on Iodized salt.

United Nations Children’s Fund, Division of Data

Analysis, Planning and Monitoring 2019. 2019.

6. Iodine Global Network (IGN). Global sco-

recard of iodine nutrition in 2020, in the general

population based on school-age children (SAC).

Ottawa, Canada; 2020 Jun.

7. Businge CB, Longo-Mbenza B, Kengne AP.

Iodine nutrition status in Africa: potentially high

prevalence of iodine deficiency in pregnancy

even in countries classified as iodine sufficient.

Public Health Nutr. 2021 Aug;24(12):3581–6.

8. IGN. Global scorecard of iodine nutrition

in 2020 - in the general population based on

school-age children (SAC) [Internet]. 2020

[cited 2022 May 14]. Available from: https://

www.ign.org/cm_data/Global-Scorecard-2020-

3-June-2020.pdf

9. Global Fortification Data Exchange. Forti-

fication Legislation Scope in Countries with

Mandatory Fortification [Internet]. [cited 2021

Jun 28]. Available from: https://fortificationdata.

org/plot-fortification-legislation-scope-in-coun-

tries-with-mandatory-fortification/

10. Dr Gayane FAYE. Cartographie des Sites

de Production Artisanale de Sel et Etude de la

Filiére Sel au Sénégal. 2018.

11. Maurel M. Etude transversale de la dispo-

nibilité des produits alimentaires de grande

consommation enrichis en micronutriment en

Mauritanie : état des lieux et analyse des goulots

d’ét ranglement à des fins de plaidoyers. 2019

Aug.

12. IGN. Program Guidance on the Use of

Iodized Salt in Industrially Processed Foods

[Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.

ign.org/program-guidance-on-the-use-of-iodi-

zed-salt-in-industrially-processed-foods.htm

13. IGN. Assessment of the potential contributi-

on of iodine from salt in processed foods in West

Africa [Unpublished manuscript]. 2021.

14. Grant F, Tsang BL, Garrett GS. Food Fortifi-

cation in West Africa. SAL 2018. 2018.

FIGURE 6

Chronology of key events that have helped to shape the Iodine agenda

in the West and Central African region

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 MAURITANIA

7

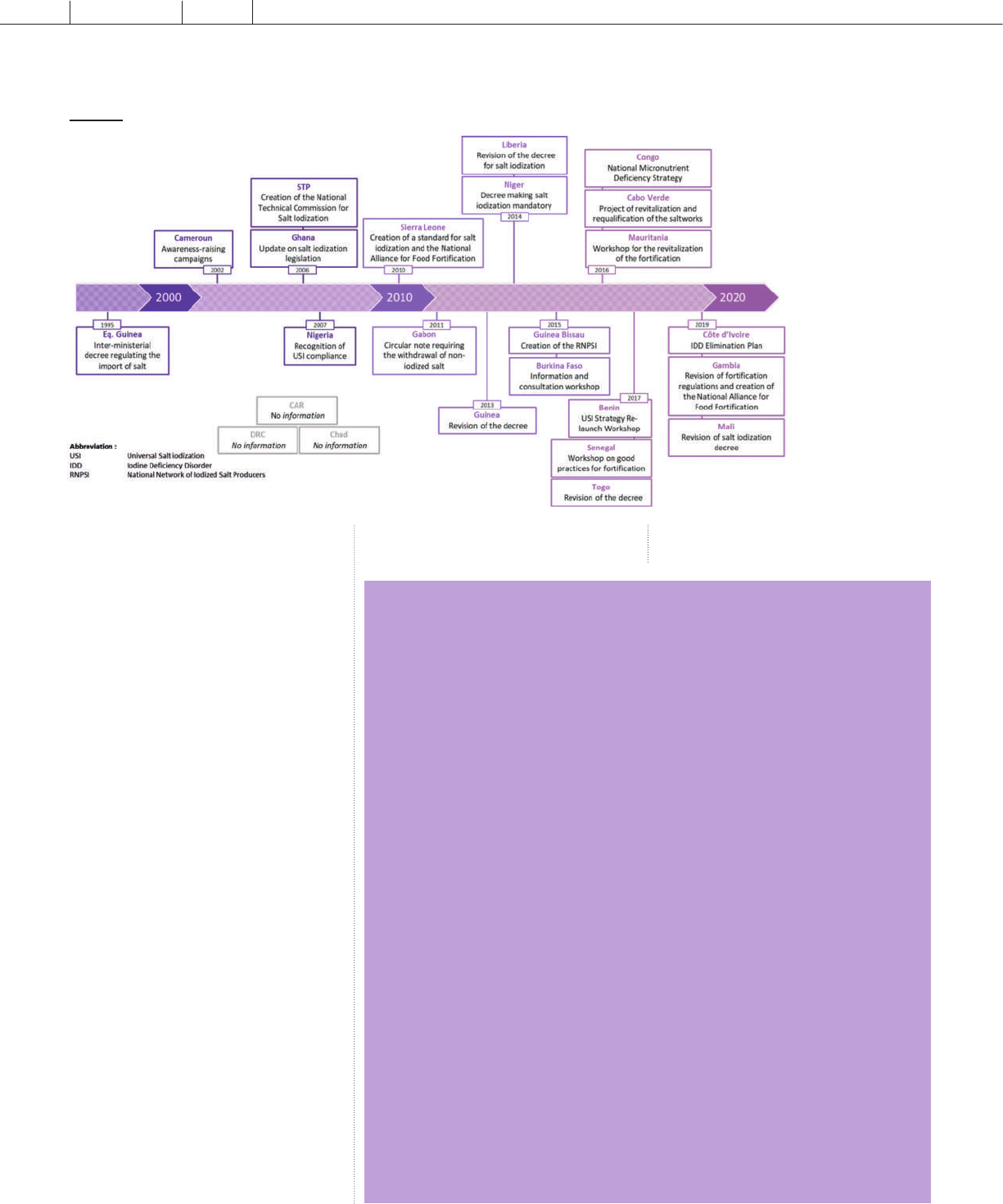

Potential for salt production

in Mauritania

Introduction

To contribute to the sustainable elimi-

nation of iodine deficiency disorders in

West and Central Africa, the United

Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and

IGN established a partnership to sup-

port national and regional efforts to scale

up and sustain universal salt iodization.

One of the initiatives was to conduct

a landscape analysis to develop a com-

mon understanding of the situation and

bottlenecks at national and regional levels.

Mauritania was selected for an in-depth

analysis because of its significant local rock

salt production and because it is one of

the countries where a joint IGN/UNI-

CEF rapid assessment is planned with the

Ministry of Health. This analysis described

the historical context of the salt iodization

program, its evolution, and its status, as

well as the main favorable and unfavorable

factors for salt iodization in Mauritania.

Specifically, the evaluation focused on the

following elements of the program: nati-

onal policies and strategies, legislation and

regulations, management of the program,

communication, use of iodized salt in

processed foods, and monitoring. A mixed

methodology was used to collect data

and information on the status of “iodized

nutrition” and on universal salt iodiza-

tion policies and programs. This involved

a literature review and interviews with

resource persons. Relevant documents

were collected through web searches,

and from national and regional develop-

ment partners. For the key informant

interviews, we identified and interviewed

national stakeholders from government,

the private sector, academia, civil society,

and development partners who have a

direct role in the implementation of the

iodine program. UNICEF country offices

and other development partners assisted in

identifying these stakeholders. (1).

Background

Mauritania's commitment

For more than two decades, Mauritania

has been committed to the fight against

iodine deficiency, which was first identi-

fied in 1995. The official adoption of the

IUS strategy by Mauritania was marked

by the signing of Decree No. 2004-034

in April 2004, making iodization of all salt

intended for human and animal consump-

tion mandatory (2). This decree covers

the entire supply chain and clearly defines

the components used for fortification,

packaging standards, impurity levels and

penalties for infractions. The iodide or

iodate iodization levels of salt are defined

as follows for the different supply steps:

• Import and export: 80-100 ppm

• Production: 50-80 ppm

• Retail: 40 ppm for 25kg bags and

25 ppm for small quantities of salt.

The Mauritanian government has also

signaled its commitment to addressing

iodine deficiency by including it in natio-

nal nutrition policies, plans and strategies.

However, there is no longer an updated

roadmap on how salt iodization should be

achieved. Only the National Strategy for

Accelerated Growth and Shared Prosperi-

ty SCAPP (2016-2030) and Multisectoral

Strategic Plan for Nutrition 2016-2025

are still active. On the other hand, there

is no national strategy to reduce salt con-

sumption.

At the same time, many actions have

been taken to support universal salt iodi-

zation: different actors have been trained,

materials have been provided to produ-

cers and to the services in charge of the

control of iodization, an association of salt

producers in Mauritania has been formed,

and the Alliance for Food Fortification in

Mauritania (AFAM) has been created but

has not yet been formalized (1).

Population status

To ensure surveillance at the household

level, qualitative analysis of household salt

using rapid test kits have been included in

the national SMART surveys. However,

national laboratories are not able to per-

form urinary iodine analysis to determine

the iodine status of the population.

Mathilde Maurel, Nutrition Consultant, Iodine Global Network, Mohamed Baro, Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF, Isselmou Ould Mohamed, Independent Consultant

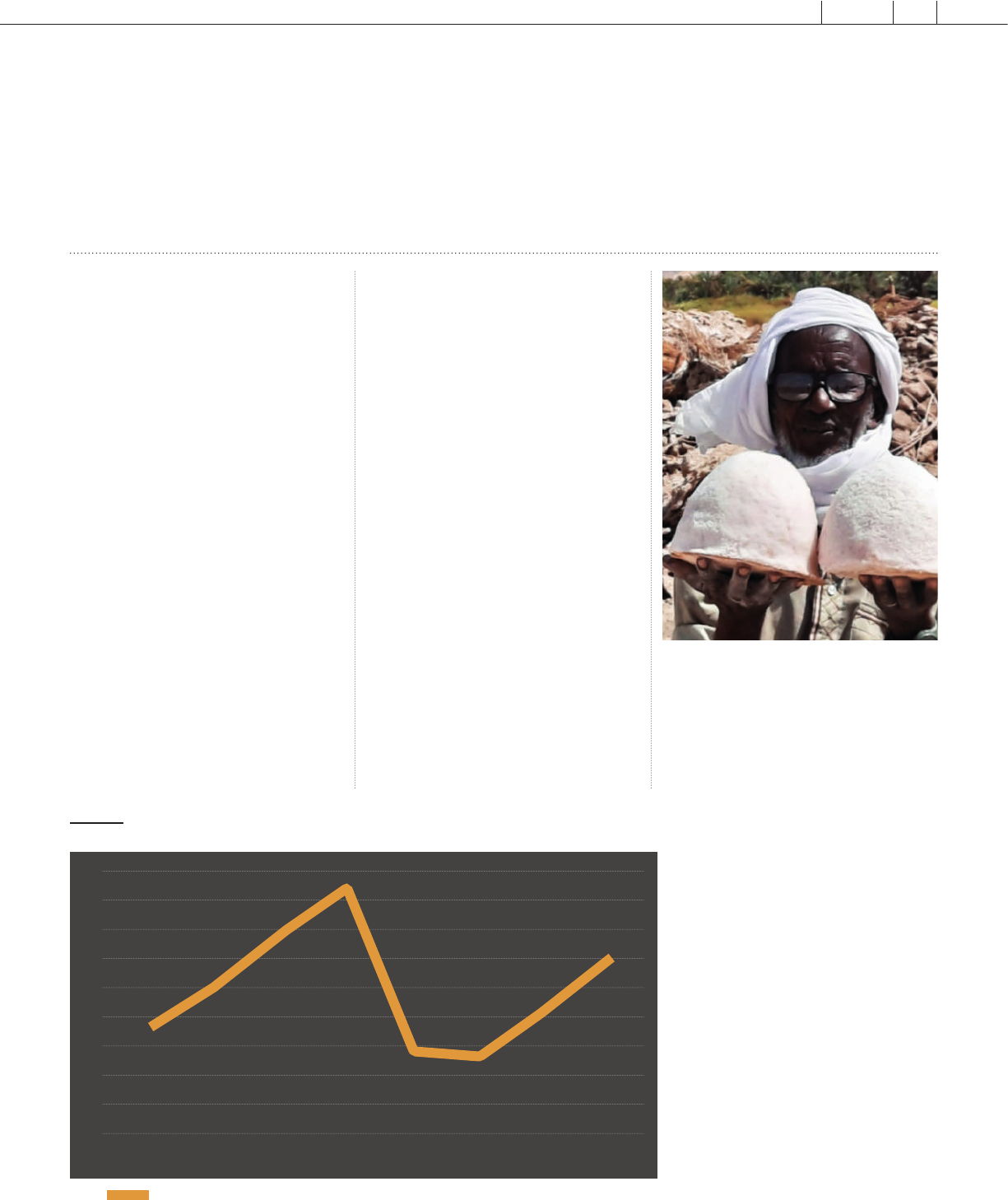

Mauritanian salt producer on the production site of N'Teret (July 2019)

According to the latest Iodine Deficiency

Disorders Survey in 2012, the median

urinary iodine level of school-aged

children was 179μg/L suggesting iodine

adequacy at a national level. Regarding

household iodized salt coverage, Maurita-

nia has experienced many fluctuations as

illustrated in Figure 1. The latest available

data indicate that 25 % of households

are covered with iodized salt (> 0 ppm).

The same survey showed considerable

variation in the proportions of households

with iodized salt by place of residence

or wealth quintile. Households residing

in urban areas were more likely to have

iodized salt, and by wealth quintile, the

wealthiest households were three times

more likely to use iodized salt (1).

Opportunities

Salt resources

Mauritania has a large salt resource with

an annual production that covers more

than its salt needs. The country is able to

produce two types of edible salt on its ter-

ritory, namely rock salt, which constitutes

80% of the total production, and sea salt

through its 600 km of coastline.

Sea salt production is mainly located

around Nouadhibou and annual produc-

tion amounts to 5,000 MT. Rock salt

extraction is carried out on 3 main pro-

duction sites whose access is often difficult

and infrastructure limited. The annual

production of rock salt amounts to 31,000

MT, which is more than double the

country's salt needs (3). The Association

of Salt Producers of Mauritania (APSM)

was created in 2005, and then the perso-

nnel of the 3 main salt production sites

were trained in salt iodization. Today, the

APSM is still functioning and continues

to be committed to salt iodization but

believes that the lack of government con-

trol and the importation of non-iodized

salt from neighboring countries creates

unequal conditions and discourages its

members from iodizing their salt.

However, given that the number

of rock salt producers is limited and that

most salt is centralized in the capital, this

represents a real opportunity for salt con-

solidation and iodization.

Demand from neighboring countries

Due to salt production exceeding the

country's needs, Mauritania can export

part of its production. The main impor-

ters of Mauritanian salt are Côte d'Ivoire

and Mali, and negotiations are underway

to expand exports to the Democratic

Republic of Congo.

Mauritania, which was a founding

member of the Economic Community of

West African States (ECOWAS) in 1975,

withdrew in December 2000 but recently

signed a new partnership in August 2017.

This new agreement offers an interesting

opportunity to strengthen Mauritania's

trade agreements with neighboring coun-

tries and to benefit from harmonized stan-

dards on iodized salt in the region. This

could allow Mauritania to develop exports

of its salt stocks to neighboring countries

(1).

Implementation of an action plan

Following the landscape analysis carried

out in the context of the partnership

between ING and UNICEF, a work-

shop was held in Nouakchott, bringing

together the main actors in salt iodization.

After the presentation of the situation and

discussions between the different decision

makers, an Action Plan for a sustainable

revitalization of the salt iodization and

iodine nutrition program in Mauritania

was developed (4). The main key messa-

ges of this action plan have been detailed

in the box below. This action plan is an

opportunity to revitalize salt iodization

activities and renews the government's

commitment to include salt iodization as a

priority objective.

Obstacles and possible

improvements

Quality of salt

Although salt resources are important,

the quality of salt is not sufficient. The

precarious conditions of the production

sites do not allow for proper iodization of

the salt. Once the salt blocks are extracted

manually from the deposits, they are

transported to Nouakchott to be crushed

and stored in 25 kg bags. Nouakchott

wholesalers can iodize salt on demand

from customers, but iodization is not

systematic. In addition, the iodization

units provided by UNICEF are obsolete

and works in fits and starts, so wholesalers

perform rudimentary iodization using

a pierced bottle that does not allow for

homogeneous iodization of the salt (3).

Considering the centralization of salt

in Nouakchott and transportation along

three main routes that intersect before

Nouakchott, the government is studying

the possibility of setting up a centralized

iodization facility to consolidate, process

and iodize salt from the main producers.

On the other hand, there is unfair com-

petition as producers sell non-iodized sea

salt and rock salt at low prices but of poor

quality. Producers do not see the point or

the constraint of iodizing their salt if they

can sell it non-iodized (1).

FIGURE 1

Trends of household iodized salt (>0ppm) coverage between 2000

and 2018

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

DHS-2000 SMART.2008 SMART-2010 MICS-2011 TDCI-2012 MICS-2015 SMART-2018

58

50

24

53

8

25

2

8

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 MAURITANIA

Sustainable financing

The Accelerated Growth Plan requires

individual ministries to establish their

own budget line for food fortification,

including salt iodization. However, fun-

ding for the salt iodization program relies

on donors such as UNICEF and in the

past by the World Bank and the United

Nations Industrial Development Organi-

zation (UNIDO). In 2020, the Ministry

of Commerce, Industry and Tourism tried

to allocate funds to USI for an awareness

campaign, but COVID did not allow this

project to proceed (1). It is important to

encourage other relevant ministries to

include a budget line in the USI program.

Rock salt purchase and use habits

The consumption habits of Mauritani-

an households constitute a challenge in

opposition to the opportunity. Maurita-

nian diets do not include powdered salt;

women cook directly with rock salt.

In a focus group conducted in 2019,

women stated that they do not know how

to cook with powdered salt and find that

iodized salt has a bitter taste (3). These

statements indicate a need to raise aware-

ness among the population about the use

of iodized salt to increase the demand for

local iodized salt among retailers.

Legislation

There are weaknesses in the current

legislation, a revision of this decree would

be necessary to include: the use of iodized

salt in processed foods, the use of only

one type of iodine compound for for-

tification, the protocol of the method

of quantitative evaluation of iodine, the

quality certification and for the removal of

all exceptions for the use of non-iodized

salt (1).

References

(1). Amal Tucker Brown, Dedenyo Adossi, Mathilde

Maurel et Arnold Timmer, Analyse situationnelle du

programme d'iodation universelle du sel en Maurita-

nie, Septembre 2021 IGN et UNICEF

(2). Ministre de la santé et des affaires sociales,

2004. Décret mau 86862 n°034 - 2004 Portant

obligation d’ioder le sel destiné à l’alimentation

humaine et animale.

(3). Maurel, M., 2019. Étude transversale de la

disponibilité des produits alimentaires de grande

consommation enrichis en micronutriment en

Mauritanie : état des lieux et analyse des goulots

d’étranglement à des fins de plaidoyers.

(4). Isselmou Ould Mohamed. Plan d’action Pour

Une Redynamisation Pérenne Du Programme

d’iodation Du Sel et de Nutrition En Iode En Mau-

ritanie, 2021 République Islamique de Mauritanie,

UNICEF, IGN.

Key Message of the Action Plan

Policy, strategy and coordination

• Advocacy for the inclusion of salt iodization in national sectoral programs.

• Organization of a data collection system (HHIS and mUIC).

• Update legislation.

• Define roles, responsibilities, and budgetary needs.

Salt production and iodization process

• Promote the creation of three economic interest groups in the production areas.

• Promote the establishment of a centralized industrial iodization facility.

Monitoring and control

• Clarify the roles and responsibilities of the institutions involved in monitoring.

• Inform customs officers about the legislation

• Require certification from exporting countries to allow salt entry.

• Involve national laboratories in the control and monitoring system.

Awareness and Advocacy

• Formalize the Food Fortification Alliance and include the Salt Iodization

Committee.

• Communicate the importance of salt iodization and legislation to retailers,

wholesalers and importers.

Rock salt extraction basin in N'teret (2019)

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 MAURITANIA

9

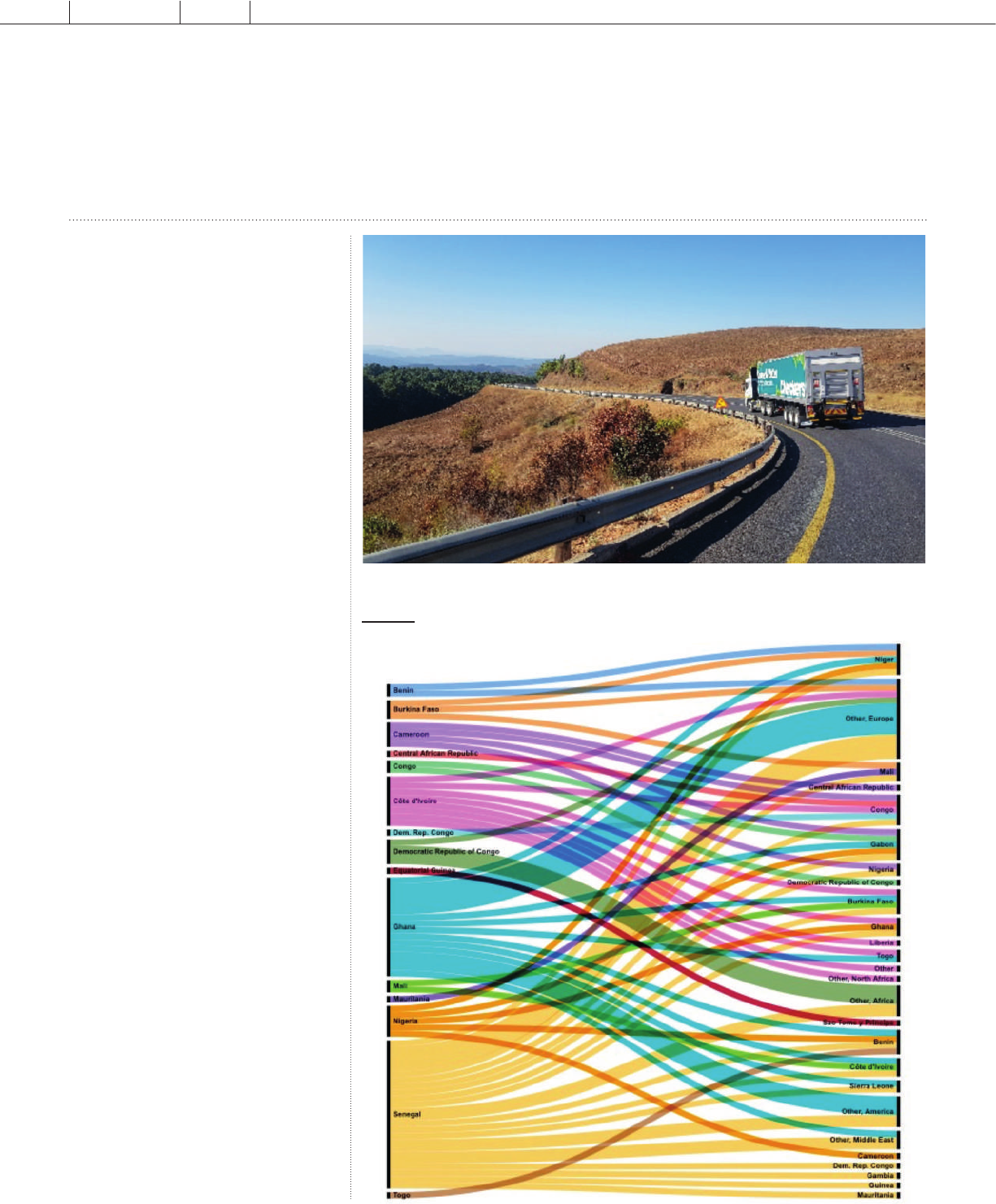

Salt trade in West and Central Africa

Trade is crucial for economic growth

and food security. West and Central

Africa (WCA) have huge potential for

trade in global and intra-regional terms.

This is particularly true for salt because

of its natural resource endowment and

intra-regional complementarities (salt-

producing and salt-importing countries).

In the WCA region, only three countries

have the natural resources to produce salt

in large enough quantities to be exported.

These are Ghana, Senegal, and Maurita-

nia. However, Senegal remains the largest

exporter of salt in the region.

In addition to above mentioned main

producing countries, Nigeria, Cameroon,

and Gabon procure raw salt, refine and

iodise it to export the higher quality salt

to neighbouring countries and beyond.

Lastly, many countries are involved in

're-exportation', which involves exporting

goods they imported without altering

them. This is particularly true of salt

transported from coastal to landlocked

countries in the region, which are subject

to multiple border checks. The trade of

salt from countries in WCA and their

destination is illustrated in Figure 1.

A study on the potential of food trade

in the Economic Community of West Af-

rican States (ECOWAS) region found that

food export by all the member countries

represented only 5% of the ECOWAS

intraregional trade. Moreover, the study

concluded that all countries of the region

are yet to fully exploit their potential in

the trade of food commodities within

the region (1). In the case of salt, despite

having sufficient natural resources within

the region to supply salt, many countries

import from outside the region. Of the

1.2 million tons of salt formally declared

and traded in the WCA region in 2020,

just under half was from a WCA country,

the remaining from outside the region

(table 1). Nigeria, the biggest importer of

salt, imported USD$77 million worth of

salt in 2020 (2). It prefers to import its salt

from outside the region, most likely due

to the ability of the region to produce en-

ough high-quality salt and, in some cases,

due to existing trade dynamics.

Amal Tucker-Brown, IGN WCA regional coordinator and Mathilde Maurel, IGN consultant

Salt truck in South Africa (Photo by Nelson Gono on Unsplash)

Adapted from UN COMTRADE

FIGURE 1

Trade of Salt from Countries in West and Central Africa

Export country

Import country

10

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 SALT TRADE

Nigeria imports the majority of its salt

from Brazil (3).

However, it is important to note that

75% of intra-regional trade is informal (4).

Informality occurs due to efforts to avoid

regulatory and transaction costs and the

deep fragmentation of supply chains, as

is the case in the salt-producing indus-

try in Senegal and Ghana. This informal

trade faces high uncertainty and costs and

therefore is not economical, preventing

investment and economies of scale. Fur-

thermore, informal intra-regional trade is

not subjected to quality controls to ensure

that the salt is adequately iodised (4).

Enhancing intra-regional trade along

with value chain development (through

increased production of quality salt and

value addition through iodisation) will not

only improve the availability of quality io-

dised salt, but it is also believed to contri-

bute to economic growth and sustainable

development, as indicated in key regional

and pan African policy frameworks (4).

This stems from the fact that it creates

opportunities for economies of scale and

allows for the flow of salt from salt-pro-

ducing countries/areas to salt-importing

countries/areas. Finally, improving intra-

regional trade has also been shown to

increase foreign direct investment (5,6),

which for the salt industry would increase

the supply of quality iodised salt circula-

ting in the region for both the household

level and the food industry.

Regional trade facilitation

and barriers

African countries and the WCA countries

have long been collaborating on regional

trade agreements as part of a broader

strategy for strengthening trade ties. The

removal of formal tariff barriers should,

in theory, lead to a significant increase in

trade flows. However, much of the focus

has been put on tariff barriers to trade,

leaving out non-tariff barriers that could,

in some cases, be associated with more

constraints to trade than the formal tariffs.

A non-tariff barrier is any measure other

than a customs tariff that acts as a barrier

to international trade(7). This is likely the

case for salt, where differences in norms

and standards (in iodine levels and quality

of salt) and lengthy and costly laboratory

testing of salt at the borders can act as

important non-tariff barriers (7).

The intra-regional trade of salt has

not been examined in depth. However, in

2016, the European Centre for Develop-

ment Policy Management reviewed the

agricultural and food trade in ECOWAS.

The review found that part of intra-regio-

nal trade flows through main regional cor-

ridors. This main West African transport

network (i.e., the West-East Trans-

Sahelian Highway between Dakar and

Ndjamena, the Trans-Coastal highway

between Dakar and Lagos and the inter-

connecting North-South corridors) serves

extra-regional, intra-regional and national

trade. Therefore, the smooth functioning

of these corridors is of great importance

for trade in the region. Additionally, they

also found considerable intra-regional

trade flow outside these main regional

corridors. This applies to trade that occurs

around border areas and where produc-

tion basins are not in the direct vicinity of

a corridor, as is often the case for salt.

Finally, the time it takes to get goods

from a producer to a buyer is an impor-

tant determinant of trade costs (8). Accor-

ding to the World Bank's annual Doing

Business report, trading in several African

countries requires three times as many

days, nearly twice as many documents and

six times as many procedures compared to

high-income economies (9). Every extra

day it takes in Africa to get a consign-

ment to its destination is equivalent to a

1.5% additional tax (9). This increase in

cost will increase the cost of iodised salt

that is formally imported and increase the

informal trade of salt that is more likely to

be inadequately iodised.

Therefore, to increase the availabi-

lity of quality iodised salt in the region,

a more in-depth analysis of the trade

barriers and facilitators is needed to design

and implement policies to promote intra-

regional trade, identify trade facilitation

initiatives and support value chain deve-

lopment of iodised salt (9).

Harmonisation of salt standards

As mentioned above, standards and norms

can act as an important non-tariff barrier

to trade. Therefore, to facilitate the regi-

onal trade and distribution of iodised salt,

a workshop was organised in late 2013 to

reach a consensus on and plan the process

From Quantity To

(Region) (MT) (Countries)

Senegal 402,419 Burkina Faso, The Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic

Republic of Congo, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea,

Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone

Ghana 130,550 Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon, Niger,

Sierra Leone, Togo

Mauritania 1,285 Mali

Other WCA country 4,628 Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African

Republic, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic

of Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Liberia, Mali, Niger,

Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe

Sub-Total WCA region 538,882

Africa (not WCA region) 118,495 Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mauritius, Namibia,

Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia

The Americas 376,438 Antigua and Barbuda, Brazil, Canada, Chile, USA

Asia 35,367 Bangladesh, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia,

Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Turkey

Europe 14,723 Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France,

Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxem-

bourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain,

Switzerland, United Kingdom

Middle East 35,097 Bahrain, Israel, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia,

United Arab Emirates

North Africa 26,446 Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia,

Oceania 25,039 Australia

Others 0.28 Others

Sub-Total 631,605

Non-WCA region

Total 1,170,487

TABLE 1

Import of salt into West and Central African countries from within

and outside the region in 2019 (2)

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 SALT TRADE

11

for harmonising standards for fortified

wheat flour, vegetable oil and iodised salt

across the entire 15-member ECOWAS

community through the ECOWAS Har-

monization Model (ECOSHAM), the fra-

mework for aligning commodity standards

in the region (10). Furthermore, in 2015,

ECOWAS published its salt iodisation

norms (ECOSTAND 48:2015), stating

that adopting a harmonised regional stan-

dard for food-grade salt would facilitate

trade globally and within ECOWAS.

The ECOWAS norm states the ma-

ximum and minimum levels for the iodi-

sation of food-grade salt along the supply

chain. Iodine in salt must not be less than

50 mg/kg at the point of production, 30

to 60 mg/kg at importation/exportation

and 20 to 60 mg/kg at wholesale and

retail levels.

The ECOWAS norm also provides

compositional and quality specifications

for fortified food grade salt. These include

the moisture level, sodium chloride level

(to define purity) and limits of impurities.

Hygienic conditions under which salt

should be produced and handled throug-

hout its distribution, packaging materials,

labelling and methods for testing compli-

ance are also provided. The ECOWAS

norm recommends that food-grade iodi-

sed salt be produced only by producers

with the requisite knowledge and neces-

sary equipment for processing quality salt,

dosing with iodine and ensuring thorough

mixing to obtain a homogeneous mixture.

The ECOWAS member states were

encouraged to adopt the regional ECO-

WAS norm on fortified food grade salt,

replacing their existing legislation/stan-

dard/norms. However, only Senegal has

adopted the ECOWAS norm. There is no

clarity why the other countries have not

adopted the ECOWAS norms, and many

have remained faithful to the WAEMU

norm, which has slightly different iodine

levels along the supply chain (Figure 2).

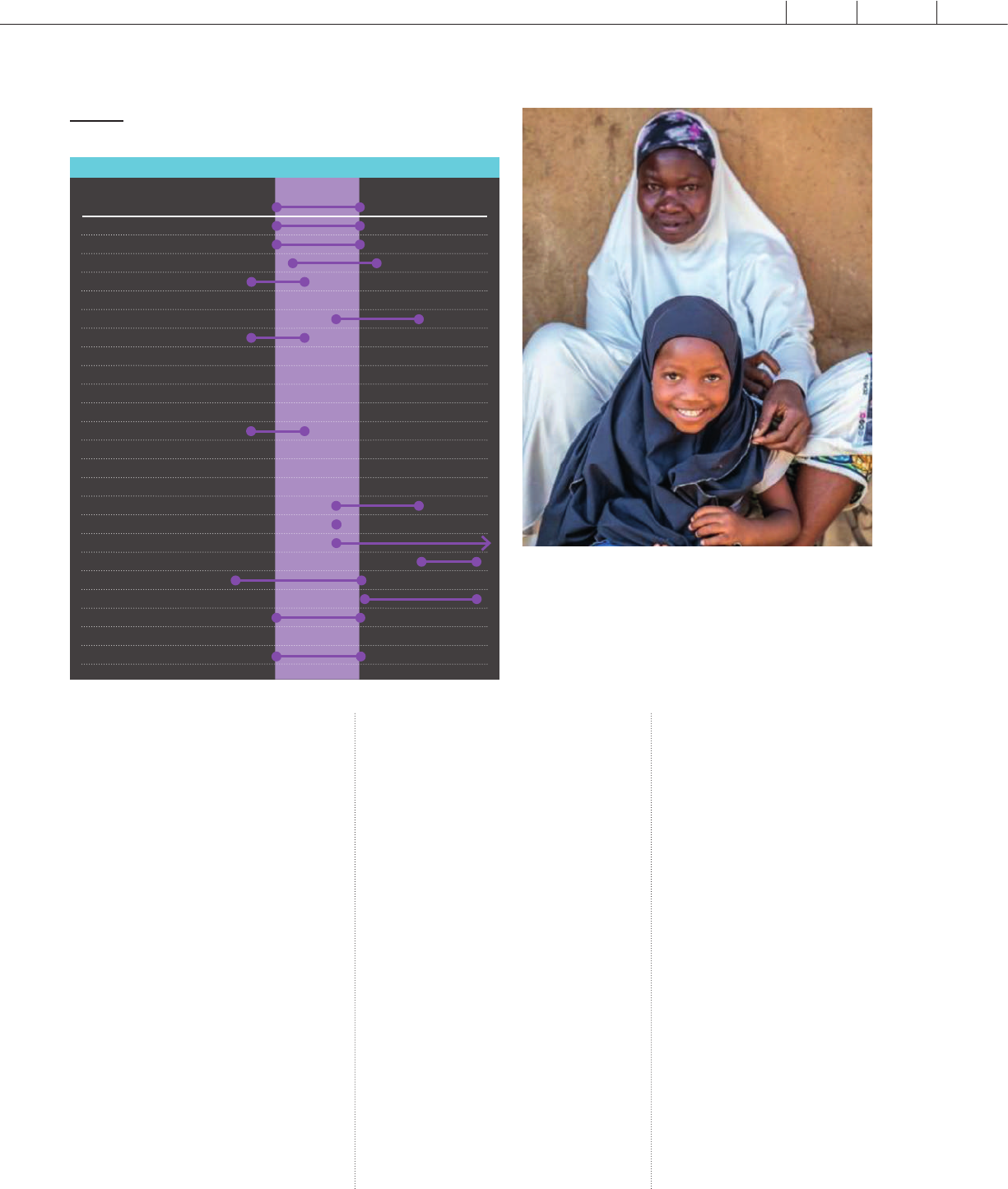

The import level of iodine (along

with the quality parameters) is signifi-

cant in the trade of iodised salt. Figure 3

shows the difference in the import level

of iodine. For most countries, there is an

overlap in the iodine level; therefore, har-

monising the standards regarding iodine

level and quality of salt would not signi-

ficantly change the amount of iodine in

the salt in each country and could remove

a potentially difficult non-tariff barrier to

trade.

Production Importation Wholehouse/ Retail

> 50 ppm 30–60 ppm 20–60 ppm

30–60 ppm 30–60 ppm 20–60 ppm

ECOWAS

WAEMU

FIGURE 2

ECOWAS and UEMOA norms at the production, import and retail levels

12

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 SALT TRADE

© UNICEF/UN0443455/Dejongh

© UNICEF/UN0418066/ Vincent Tremeau

ECOWAS is currently developing a

certification project to identify products

that comply with its norms. However,

salt is presently not part of this project.

Combining this regional certification

system with innovative technology such

as blockchain technology could help salt

producers obtain iodine levels and salt

quality certification. The certificate can be

verified along the supply chain, assuring

salt buyers that the salt has been approved.

This could minimise the need to assess the

salt at each border.

In summary, most WCA countries

import iodised salt to meet their national

salt requirements, and the region can meet

these needs. However, the intra-regional

trade of salt is below its potential. The-

refore, a more in-depth assessment of the

trade barriers and facilitators is needed to

design and implement policies to promote

intra-regional trade, identify trade facilita-

tion initiatives and support the value chain

development of iodised salt (9).

Improving the intra-regional trade will

contribute to the regional economy and

could improve the supply and demand

of iodised salt both for salt-producing

countries and salt-importing countries due

to the symbiotic relationship between the

countries.

References

1. Ibitoye O. Assessment of the potential level of

food trade in the ECOWAS region. 2020;18.

2. UN Comtrade | International Trade Statistics

Database [Internet]. [cited 2022 May 14]. Available

from: https://comtrade.un.org/

3. Nigeria | Imports and Exports | World | Salt;

sulphur; earths and stone; plastering materials, lime

and cement | Value (US$) and Value Growth, YoY

(%) | 2008 - 2020 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022

May 14]. Available from: https://trendeconomy.com/

data/h2/Nigeria/25

4. Torres C. Overview of trade and barriers to trade

in West Africa. 2016;(195):94.

5. Ibitoye O, Ibitoye AL. Determinants of intra–ECO-

WAS regional food trade: An augmented gravity

model approach. 2020;18.

6. Were M. Differential effects of trade on economic

growth and investment: A cross-country empirical

investigation. JAT. 2015;2(1–2):71.

7. Non-tariff barriers [Internet]. The Institute for

Government. 2017 [cited 2022 May 14]. Available

from: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/

explainers/non-tariff-barriers

8. Hummels DL, Schaur G. Time as a Trade

Barrier. American Economic Review. 2013 Dec

1;103(7):2935–59.

9. Hoekman B, Shepherd B. Who profits from

trade facilitation initiatives? Implications for African

countries. JAT. 2015;2(1–2):51.

10. Grant F, Tsang BL, Garrett GS. Food Fortification

in West Africa. SAL 2018. 2018;

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 SALT TRADE

13

FIGURE 3

Comparison of iodine levels for imported salt by

country in West and Central Africa

Countries Import iodine level (ppm)

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

ECOAW and UEMOA

Benin

Burkina Faso

Cameroon

Cabo Verde

Central African Republic

Chad

Republic of Congo

Côte d'Ivoire

Dem. Rep. of Congo

Equatorial Guinea

Gabon

Gambia

Ghana

Guinea

Guinea Bissau

Liberia

Mali

Mauritania

Niger

Nigeria

Sao Tome y Principe

Senegal

Sierra Leone

Togo

© UNICEF/UN0376940/Esiebo

Lessons from Togo on sustainable

USI

Dédényo Adossi, Consultant, Iodine Global Network; Mamatchi Mélila, Lecturer, Université de Lomé; Komlan Kwadjode, Nutrition specialist, UNICEF Togo;

Mouawiyatou Bouraima, Head of Nutrition Division, Ministry of Public Health and Hygiene

Togo, a francophone country located on

the Gulf of Guinea, does not produce

sufficient salt but imports it mainly from

neighboring Ghana. The first national sur-

vey on the situation of iodine deficiency

was carried out between 1982 and 1986,

and showed a goiter prevalence of 18%

among the Togolese population (1). This

alarming rate prompted the generalized

distribution of iodized oil in the period

1990-95 to prevent Iodine Deficiency

Disorder (IDD). National legislation on

universal salt iodization (USI) was adopted

in 1996 (Arrêté interministériel N°76/

MSP/MCPT, 1991), and updated in 2017

(Arrêté N°124/2017/MSPS/MCPS/

MEPSFP/MEF ) to comply with the new

Economic Community of West African

States (ECOWAS) standards. Results of

the USI program until 2005 were remar-

kable, thanks to consistent funding, strong

multisectoral coordination and leadership

by the Ministry of Health. In just ten ye-

ars the household coverage of iodized salt,

which was almost nonexistent in 1995 (at

1%), was universal by 2005 (at 92%) (2,3).

Consequently, the median urinary

iodine concentration (mUIC) measured

through a national survey in 2005, re-

vealed a mUIC of 171,4μg/l in schoold

age children, which is considered to be

in the adequate range (2). Unfortunately,

this is the only existing data on iodine

status and no survey has taken place since.

As of 2005 the situation started to reverse.

Following a fall in financing by partners,

monitoring and sensitization activities

became more difficult to maintain. This

proved a barrier to the sustainability of the

program, and there was a steady decline in

the general trend of household coverage

of iodised salt, which decreased to 81% in

2010 and 63% in 2017 (4,5).

A stocktaking exercise undertaken by the

Nutrition Division in 2013 showed a lack

of surveillance of salt iodization at borders

and the necessity to clarify roles and

responsibilities of different stakeholders

(6). This prompted the development of

guidelines for the surveillance of iodized

salt, the supply of portable WYD spectro-

meters for the quantitative assessment of

iodine in salt at the border and of labora-

tory equipment for the national reference

laboratory (6).

14

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 TOGO

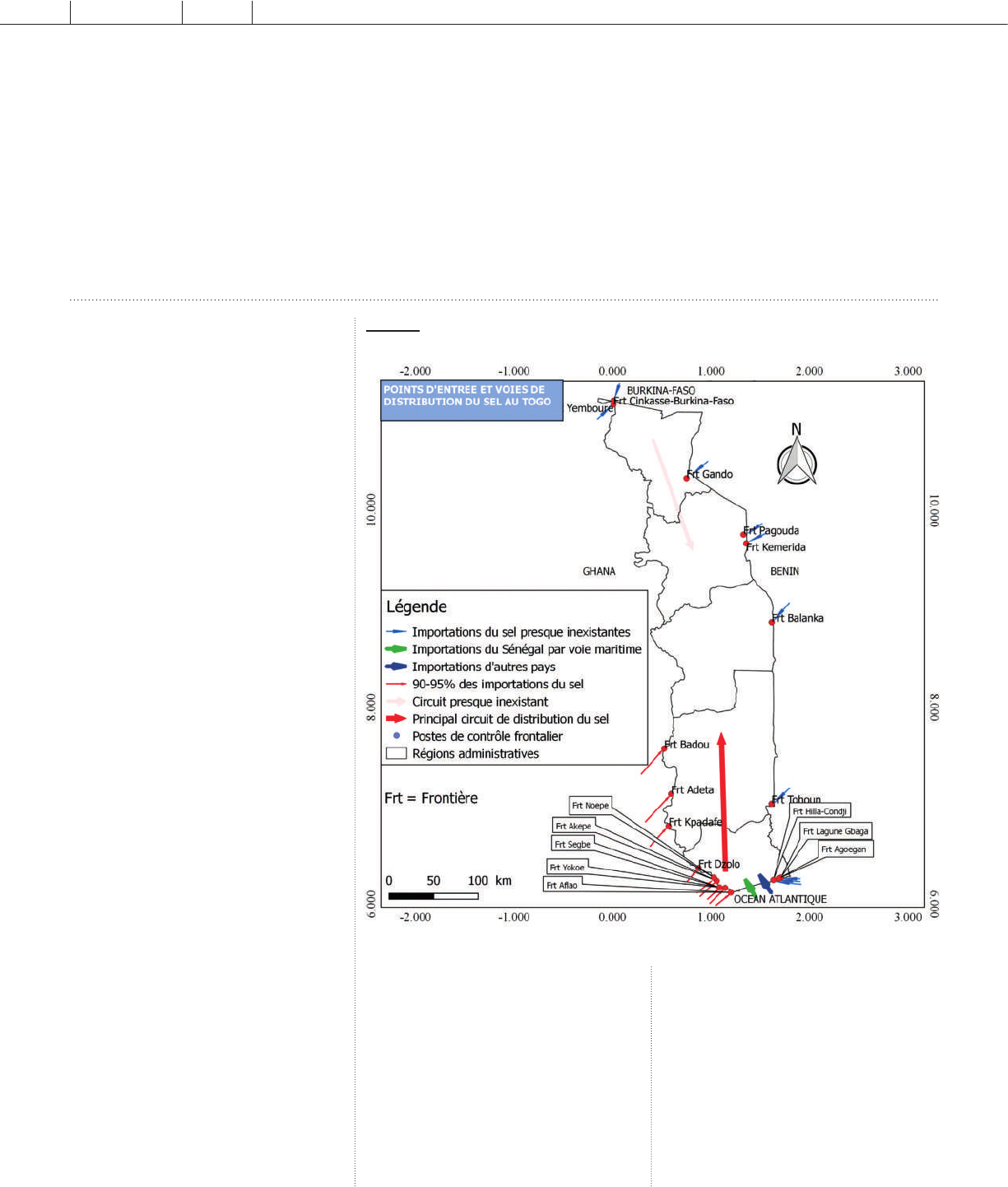

FIGURE 1

Location and distribution of the main salt import and distribution routes

in Togo (7)

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 TOGO

15

However, these efforts were not sustained,

the WYD spectrometers was provided to

official entry points only, while there is

illegal entry of salt via the multiple dirt

roads along the 600 KM border with

Ghana (7) (see figure 1). Furthermore,

when controls were conducted, their

results were not necessarily used by the

decision makers and leaders of the USI

program.

In 2021, as part of the IGN/UNI-

CEF regional partnership, a situational

analysis of the iodization program in Togo

was conducted together with the Govern-

ment to understand the low availability of

iodized salt in the savanna regions. The

study included 21 importers/wholesalers

and 61 retailers in the markets as well as

the collection of 82 samples of cooking

salt. Findings show that more than one

in two respondent (58%) does not know

about the legislation on salt iodization.

For 20% of retailers, color was the quality

criterion for iodized salt, while for whole-

salers, color (18%), price and iodine con-

tent (18%) were the determining factors.

Iodine content was important only for

7% of retailers and 4.5% of wholesalers.

A staggering nine in ten (93%) retailer

and one in two wholesaler (54%) does

not control the quality of salt, including

iodine level, before purchase.

Retailers declare that 43.3% of

purchased salt is iodized, while it reaches

56.7% for wholesalers, the adequacy of

the iodine level was not possible as only

qualitative assessments were possible at

the purchase sites. However, the overall

mean iodine content of all samples (up

to 12.94 ppm) was below requirements

(of at least 20 ppm in Togo). Labelling is

unreliable as salt is repackaged by 83% of

respondents. The main conclusions of the

situation analysis show that to revita-

lize the USI program in Togo, driving

demand for iodized salt while ensuring

the supply of quality imported iodized

salt by importers and its control at borders

will be instrumental. Continuation of

sensitization of all stakeholders will also be

necessary to ensure adequate household

coverage of iodized salt.

From the Togolese experience, it is

clear that the sustainable success of the

USI program can be highly dependent

on synergy between the different sectors

involved. A dedicated domestic budget

line will help avoid dependence on fun-

ding from partners. Effective monitoring

associated with actions are essential and

there must be strong linkage between the

USI coordinating team and the importers.

These are important elements to consider

in developing and implementing a suc-

cessful sustainable USI strategy.

References

1. Doh A, Adjaka Y, Quashie K, Francois C, Ame-

la S, Agbe A, et al. Document national du Togo

prepare pour la Conférence Internationale sur la

Nutrition: Rome. In Rome; 1992. p. 37.

2. Ministère de la santé. Evaluation de la lutte

contre les troubles dus a la carence en iodie en

2005 au Togo. 2006.

3. Ministère Du Plan et de l’Aménagement du

Territoire, UNICEF. Enquête Nationale sur la

Situation des Enfants au Togo en 1995 (MICS-

Togo-96). 1996.

4. Ministère auprès du Président de la Républi-

que, chargé de la Planification, du Développe-

ment et de l’Aménagement du Territoire, Direction

Générale de la Statistique et de la Comptabilité

Nationale, UNICEF. Togo - Suivi de la situation

des Enquête par grappes à indicateurs multiples

enfants et des femmes. 2010.

5. Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes

Economiques et Démographiques (INSEED),

UNICEF. TOGO MICS6 - Enquête par grappes à

indicateurs multiples 2017. 2019.

6. Ministère de la santé. Guide de contrôle de

qualité du sel alimentaire au Togo. 2013.

7. Adossi D. Etude du système de distribution

et de contrôle du sel iode au Togo. Institut poly-

technique LaSalle Beauvais (France); 2015.

© UNICEF/UN0428853/Tremeau

© UNICEF/UNI282238/Pudlowski

16

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 NIGERIA

Salt value chain analysis in Nigeria

Introduction

Numerous studies have clearly establis-

hed that fortification of salt with iodine is

an effective means of controlling iodine

deficiency. Since the effective introduc-

tion of salt iodization in Nigeria in 1993,

the sustained salt iodization program

has ensured an adequate iodine status

among the whole the population. Nigeria

achieved global recognition in 2007 as

the first African country to be compliant

with universal salt iodization (USI) due

to sustained high levels of salt iodization

coverage (from a level of <40% in 1993)

to 95% or higher. Despite the reference to

salt for food processing in the original de-

finition of universal salt iodization (USI),

Nigeria’s USI program does not explicitly

address food industry salt. This may affect

program impact and sustainability, given

the increasing consumption of processed

foods triggered by higher income, urbani-

zation, and lifestyle changes. This affects

the source of salt and potentially iodized

salt among the population. It is against

this backdrop that a salt value chain ana-

lysis was conducted. It had as objective:

(a) assessment of the contribution of salt

contained in industrially processed foods

to salt and iodized salt consumption of the

population; and (b) to identify the pos-

sibilities of expanding the salt iodization

strategy to include processed foods.

Methodology

The methods used include a review of

reports and other documents and key

informant interviews (KII). Documents

that were reviewed include government

agency and partners’ reports on the salt si-

tuation. Structured face-to-face interviews

with food manufacturers and in-depth in-

terviews with processed food wholesalers

and retailers were conducted and food

labels were checked in the supermarkets

and local markets.

Key findings

Even though Nigeria has large salt depo-

sits in some states including Benue, Cross

River, Ebonyi, Abia, Taraba and Nasara-

wa states, there is no large-scale mining

of these salt deposits. As such, most salt

manufacturers import salt from Brazil,

Namibia, South Africa, China, Australia,

India and the USA. Nigeria’s imported

salt worth increased from N4.5bn to

N4.8bn (1). Nigeria imports from Brazil

were estimated at US$33.79 million

during 2019 (2).

Wasiu A. Afolabi, Professor, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria; Francis T. Aminu, Aliko Dangote Foundation, Lagos, Nigeria

TABLE 1

Manufacturers, Marketers and Distributors of Salt

in Nigeria

Name of Production Product Domestic Export

Industry Capacity Market Market

NASCON 2450MT/Day Table Salt Nigeria Benin

Industrial Salt

Royal Salt 300,000MT Table Salt Nigeria

Industrial Salt

Mr Chef N/A Table Salt Nigeria

JOF Salt 108,000 Industrial Salt Nigeria Ghana

MT/Month

© UNICEF/UN0377181/Esie

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 NIGERIA

17

Raw salt is imported by major salt manuf-

acturers from Brazil, Australia, Tunisia,

and Namibia. All salt imported from

Brazil, Tunisia and Namibia is not iodized

and so it is the responsibility of the repa-

ckaging companies to fortify imported salt

with iodine before selling to the consu-

mers. Countries of export for salt from

Nigeria include Benin Republic, Niger

Republic, Cameroon, Ghana, and Chad.

All food grade salt produced for domestic

use and export is iodized.

There are three major salt manufactu-

rers producing salt in Nigeria for com-

mercial purposes (Dangote Salt, Royal

Salt, and Mr. Chef Salt) and one that pro-

duces salt for food industries (JOF) (Table

1). Dangote and Royal Salt produce table

salt and industrial salt while Mr. Chef only

produces table salt. JOF salt, at the time

of the assessment, did not have salt in the

open market but only produced industrial

salt that was supplied to food companies

for cornflakes, bouillon, and seasoning

production, with Nestle Foods as a major

client.

There are two major channels of

salt distribution in Nigeria. One is direct

from the factory to the large consumers,

such as the food processing industries and

livestock farms. The second channel is

from the factory to major distributors or

wholesalers who also sell to retailers and

who in turn sell to consumers. Interestin-

gly, medium- and small-scale industries as

well as fisheries and livestock farms also

procure salt from major distributors and

subdistributors. As shown in Figure 1, salt

is procured from the factory by major

distributors who are often referred to as

dealers who move the supplies to their

warehouses and outlets. Subdistributors

and wholesalers also procure from the ma-

jor distributors for display in their stores/

shops. At times they supply directly to

their clients on request. Retailers procure

salt from subdistributors or distributors

and then sell to the consumers. Distribu-

tors and subdistributors at times supply salt

directly to food processing companies and

fishery and livestock farm.

The survey indicates that food pro-

cessing companies, wholesale distributors

and marketers are the major consumer of

salt from the industries. As shown in Table

2, food processing companies procure

about 26% of the salt. Wholesale distri-

butors also constitute about 26% of the

salt consumers while supermarket/mall,

retailers and livestock farms were less than

20% each. Supermarkets, malls, and stores

are the major salt procurement clients,

followed by fisheries and livestock farms.

Iodized salt constitutes about 99% of

the salt in the market while non-iodized

salt is about 1% and are not displayed

openly for sale. Dangote Salt (50kg) sold

for N4400 - N5000 while Royal Salt

(50kg) sold for N4300 - N4900. The

salt procurement capacity of distributors

and marketers of salt varies, and ranges

between 1000 and 50,000 bags for a range

of 1 to 6 times per month. The majority

(70%) of the distributors and marketers

procure less than 5000 bags while others

constitute 10% each. Dangote Salt, Mr.

Chef Salt and Royal Salt continue to do-

minate the market in Nigeria as they were

ranked first, second and third, respectively

(Table 3). Although, clients in Lagos ran-

ked Mr. Chef salt first and Dangote Salt

second, indicating that ranking of salt is

location specific.

The major consumers of salt in Nige-

ria are food processing industries, super-

markets and malls, wholesale distributors,

retailers, and livestock industries (Table 4).

For table salt, the domestic market for the

product can be found in all local markets,

supermarkets, and shopping malls while

the export market is in Benin Republic.

For industrial salt, the local market

includes soap manufacturers, seasoning

companies, noodle producers, margarine

producers and animal feed manufacturers.

FIGURE 1

Salt distribution channel

Salt Factory

Major Distributors

Sub Distributor

Retailer

Consumer

Food processing

Companies

Fishery and Live-

stock Farms

TABLE 2

Major Consumers of Salt (Survey 2021)

Name Frequency (n) Percentages (%)

Food Processing Industries 10 25.6

Pharmaceuticals 0 0

Supermarket/Mall 7 17.9

Wholesale Distributors 10 25.7

Retailers 6 15.4

Livestock 6 15.4

Conclusion

Although food grade salt is being produ-

ced by four salt manufacturers in Nige-

ria, there is a need for adequate policy

to address fortification compliance and

fluctuation in price. Challenges faced by

marketers and distributors ranges from

high pricing, untimely delivery by the

manufacturers and logistics problems. The

Standard Organization of Nigeria (SON)

and the National Agency for Food, Drug

Administration and Control (NAFDAC)

are the agencies involved in the monito-

ring of salt business in the major salt mar-

kets. Salt distribution follows two major

channels; from factory to major distribu-

tors who procure salt from factories and

supply either directly to food processing

companies and or Sub- distributors and

wholesalers who supply to retailers and

then finally to consumers.

The analysis also revealed that some

factories also supply direct to food pro-

cessing companies indicating that food

processing companies, wholesale distribu-

tors and marketers are the major con-

sumers of salt while supermarkets, malls

and stores are the major salt procurement

clients, followed by Fisheries and livestock

farms. Various industries that procure salt,

cut across cosmetics industries, Biscuits

and sweet industries, hotels, kitchen and

restaurant, bread and bakery industries,

supermarkets, malls and stores and fishe-

ries and livestock farms. There is a need

to encourage more salt manufacturers in

the market to increase competition, ade-

quate monitoring of industries to ensure

compliance and regulate price of salt to

prevent fluctuation. However, the con-

tribution of industrially processed foods

to salt and iodine intake and the possible

impact of salt reduction on iodized salt in-

take remain to be quantified. To improve

Nigerian USI programs, further data are

required on processed food consumption

across population groups, iodine contents

of food products, and the contribution of

processed foods to iodine nutrition.

References

1. National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), UNICEF,

and UNFPA (2013), Nigeria Multiple Indicator

Cluster Survey (MICS) 2011

2. United Nations COMTRADE ( 2021) https://

tradingeconomics.com/nigeria/imports/brazil/salt-

including-table-dentrd-pure-sodium-chloride

TABLE 3

Salt Ranking by Marketers and Distributors (Survey 2021)

Salt Product 1st % 2nd % 3rd %

(n) (n) (n)

Dangote Salt 7 70 3 30 – –

MR. Cheff Salt 3 30 3 30 4 40

Royal Salt – – 4 40 4 40

Total 10 100 10 100 8 100

TABLE 4

Large Scale Salt Procurement Clients (Survey 2021)

Name Frequency (n) Percentage (%)

Cosmetics Industries 1 2.5

Biscuit and Sweet Industries 2 5

Kitchen and Restaurant 8 20

Hotels 2 5

Bread and Bakery Industries 6 15

Supermarkets, Malls and Stores 12 30

Fisheries and Livestock Farms 9 22.5

© UNICEF/UN0396203/Owoicho

18

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 NIGERIA

IDD NEWSLETTER MAY 2022 CHAD

19

Salt iodization in Chad

Chad is a landlocked country and almost

all salt consumed is imported from

Cameroon, Egypt, Libya and/or Sudan

with small artisanal salt producers in the

northern part of the country. A national

survey conducted in 1994 showed a goiter

prevalence of 63% and that 1% of the po-

pulation was affected by cretinism. Iodine

deficiency was hence declared a public

health issue and iodization of salt for hu-

man and animal use was made mandatory.

However, the lack of financial means has

impeded the application of legislation.

With the declaration of iodine deficiency

as a public health issue in 1994, legislati-

on was put in place, defining the level of

iodization, monitoring, and surveillance

of household salt. Iodization is mandatory

for all salt for human and animal con-

sumption, but since the legislation does

not specifically mention locally produced

salt and salt for export, many erroneous-

ly believe these salts do not need to be

iodized.

Universal Salt Iodization was

integrated in several national nutrition

policies and plans. Decisions related to

iodine nutrition are deliberated at the

level of the National Council of Food

and Nutrition which meets once a quarter

and implemented by the executive body,

the Permanent Technical Committee on

Nutrition and Food, which is housed in

the National Directorate of Nutrition and

Food Technology (DNTA). The DNTA

is an organ of the Ministry of Public

Health and National Solidarity, who

oversees the coordination, follow-up, and

monitoring of iodine nutrition actions.

The demographic and health surveys,

as well as the SMART surveys underta-

ken in the country since 2000 show an

upward trend for the period 2000-2014,

when the use of household iodized salt

increased from 58% in 2000 to 82%. This

had direct consequences on the iodine

status of the population. The latest data

on iodine status dates to 2003 and showed

that school aged children (aged 6-12

years) had an adequate iodine status, with

a mUIC of 213μg/L. Between 2014 and

2019 there was a sharp fall in the use of

iodized salt, down to 65%, before it slow-

ly went up again, to reach 70% in 2021

(Figure 1).

An iodized salt evaluation mission

conducted in 2014, shows that salt from

Cameroon and Egypt transiting through

Cameroon was correctly iodized, while

salt imported from Sudan or locally pro-

duced was either poorly iodized or not

iodized at all. Recent surveys have

found little variation in access to io-

dized salt by urban/rural but did find

variation by region due to the origin

of the salt. For example, in the East,

the salt comes from Sudan, where it

is not iodized, leading to low use of

iodized salt in this region. The 2019

MICS did show differences per wealth

quintile, with the richest households

more likely to use adequately iodized

salt. Domestic production of non-

iodized salt is growing significantly in

the provinces of Borkou, Ennedi and

Tibesti, but unfortunately no action is

undertaken to ensure compliance with

the country's salt iodization legislation.

While the general population has

some level of awareness of the im-

portance of iodized salt, there is some

confusion as some bags of salt are

Sansan Dimanche, International Nutrition Consulting (INC-Tchad); Viviane Djoret, UNICEF Chad; Mahamat Abdelkerim, Nutrition and Food Technology

Directorate (MOH, Chad);

Djibril Cisse, UNICEF Chad

FIGURE 1

Availability of iodized salt at household level through different surveys

in Chad

85

80

75

70

65

60

55

50

45

40

MICS

2000

DHS

2004

MICS

2010

DHS

2014

SMART

2017

SMART

2019

SMART

2020

SMART

2021

58

Salt iodization

65

74

82

53.5

52.7

53.5

60.7

69.8

Clumps of non-iodized salt from Boudo

Iodized salt for a bright future for children in

Chad

History of the salt trade in Chad

Local production and salt trade has been linked to caravanners, who would

insure the transport of salt across long distances. The entire salt route was